Ever since the Ukrainian crisis started, the relations between myself and my Russian friends have suffered quite a bit. Depending on the person, we have either agreed not to talk about politics, wrangled every time we are in contact (but still remain friendly to each other, underlining that we have nothing against each other personally), or stopped speaking to each other after yet another row about who’s lying the most – Russians or “the West”. The Malaysian plane crash has only made it worse, with Russians blaming Ukraine (and the U.S.) about the catastrophe; and Western media pro-Russian rebels (and Putin). Although I generally consider the people I am in close terms with both intelligent and and skillful critical thinkers, I am finding it more and more difficult to find a common language with them. It is because at the moment they are not only critical of the Russian national TV and its ouvertly “Western-looking” counterparts like BBC Russia and Golos Ameriky, but every single media outlet. In short, they have stopped believing in objective journalism. They are determined that every journalist, regardless of their background or media affiliation, is a puppet of their emplyer. As a good friend of mine pondered the other day, “even the so-called independent journalists must be paid by someone…”. The current Russian public is certain, that everyone can be bought: the news anchor of RT who resigned on air a few days ago (obviously the Americans just paid her more!), members of the research team that are trying to find out what happened to the plane that was shot down (“obviously they want to prove it was the pro-Russian rebels who did it!), et cetera. In essence, the Russian public are growing more and more prone to believing in all kinds of conspiracy theories.

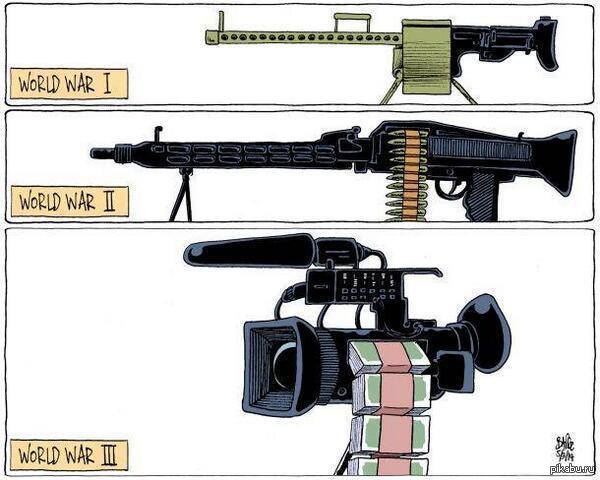

In the heads of millions of Russians the current situation in world politics looks like this: “The West”, lead by the United States and her allies (including the EU and UN and) have launched an information war against Russia. The aim of the war is to discredit Russia in all possible ways and portray it as a tyrannic and stagnated state. By doing so, citizens of those countries that used to be close allies of Russia (Georgia, Ukraine, etc.) become more and more negative and aggressive of Russia and Russians and, in the end, financed by the West, stage a coup d’etat, a so-called “colour revolution” and gain power. Russia’s influence in the world decreases and she will become weak – an easy prey for Western state-linked corporations that want to gain control over Russia’s rich natural resources. If this happens, Russia will be humiliated and stripped off all her righteous former glory. The Russian people will be forced to live in poverty, as slaves to the foreign countries, feeling ashamed of their Russianness.

According to the Russian experts, the information war started in the end of 1990s, when the Russian state had recovered from the chaotic Yeltsin period. Putin’s era has seen the Russian state growing gradually stronger and stronger, with Russian leaders becoming more independent of foreign companies and taking an active role in world politics. The elites are trying really hard to nurture a feeling of patriotism and national pride among the masses. Judging from the psychological viewpoint, painting the picture of a common enemy works more than well. However, I am beginning to think that the public’s attitude towards all media employees as potential brain-washing hit men is bringing out some schizofrenic attributes in average, peace-loving Russians. They feel the ever-present threat of the blood-thirsty Western imperialists. They feel like they can’t trust anything anyone says – who knows, maybe even their close friends or relatives are working for the other side. At the same time they are painfully aware of what is being said about Russia in Western media; things they really don’t want to believe because personally they are very fond of their country, its history and traditions. On the other hand they look around them and see poverty, exhausted fellow citizens, people who are tired of trying to make ends meet.

I discovered a fascinating website that describes the anti-Russian information war in detail (unfortunately available only in Russian). It states that the successful information war has lead to enormous gains for the West. The site includes a list of both Russian and international organisations as well as individuals that have either striken a deal with the imperialists or fallen victims to their brain-washing. Russian opposition activists, Greenpeace, Human Rights Watch and even surprising names, such as Karl Marx make the list of russophobes. What is interesting, is the re-emergence of very powerful words such as “russophobe”, “fascist” or “fifth column” in the everyday liguistic environment. Many Russians today are sure that Ukrainians are a nation of russophobe fascists. Such projection of the Soviet-era Slavic brothers is in stark contrast to both the reality and the Russian portrayal of Ukrainians only ten years ago. In addition to Ukrainians, also Georgians have gone from friends to enemies almost overnight. I wonder whether Serbs will get the same treatment if/when the country decides to embark on a road of closer collaboration with the West?

According to the official story, the Western anti-Russian information war is designed to isolate Russia and Russians from the rest of the world. What they seem to have missed is, however, the immediate isolating effect that has followed the Kremlin’s vigorous campaign against the “Western propaganda”. Even Angela Merkel famously complained that president Putin seemed to be “living in another world”. More than anything, this is a result of believing in the global international information war. It is blurring the line between fiction and reality (as a sidenote, did you hear about the theory that MH17 was, in fact, filled with corpses?), and leaving people feeling scared and paranoid as they believe they’re constantly under threat. Conspiracy theories mushroom and people reach the state where they refuse to trust anyone.

Needless to say, co-operating with such people is extremely difficult. This is why Russia–West relations have been going downhill for a good time. This is also why I believe the sanctions against Russia won’t work; in contrary, they will be used as yet another example for the Russian people, proving that the whole world is against them. Indeed, they ask, why is it that the West turns a blind eye to China’s human rights violations, not even to mention about the crimes Israel commits in Gaza? Why are they so keen to point out Russia’s shortcomings from the Sochi olympics to environmental issues? Why do they deliberately want to weaken Russia’s economy?

For them, the answer is simple: they are anti-Russian imperialists, that want to gain over Russia and her oil and gas. To let you check how brain-washed by anti-Russian propaganda you are yourselves, here’s a list of the most common lies, spreaded by the russophobe camp:

1. Russia is miserable and shameful. (Everything from Russia is of bad quality. Life in Russia is agony.)

2. West is better than Russia (more civilised, better developed, etc.)

3. Patriotism is for idiots (modern citizens should see themselves as independent world citizens)

4. Everything in Russia is getting worse (if nothing changes, e.g. a drastic political change towards Western-style liberal “democracy”)

5. Russia has no enemies. (The Cold War has ended and the biggest enemy of Russia is Russia herself)

6. The Russian ruling elites are illegitimate idiots who only care about their own bank accounts.

7. A new revolution is necessary in Russia (to get rid of the old elites for good and start afresh).

8. The state is our enemy (and anyone who works for the state is probably a corrupt bastard).

9. The Orthodox religion is bad (because it’s exacly why Russia has remained such a backward country)

10. Russia for Russians. (Which is why Russia should retreat from Caucasus and allow Chechen independence.)